Community concerns cause concrete concepts by Alison

As I left Eggcup, the community food outlet in Morecambe, I felt more than a semblance of annoyance. Their distribution of unsaleable groceries, lauded by local government executives as nothing short of a modern reworking of Jesus’ feat of brilliance with loaves and fishes left me deflated that my appointment with them was largely unproductive. There was plenty of food, but nothing I could use because of dietary problems. With no refrigerator or freezer and a disability affecting my hands, going to the quasi supermarket was rewarded with two packets of cereal bars.

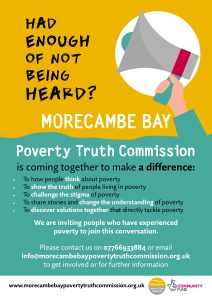

I folded away the optimistically large carrier bag into my pocket and continued down Clarendon Road, passing the large windows of Eggcup en route. I paused to look at a brightly coloured poster hung in the window. The poster had a cartoon-style megaphone to attract attention and its eye-catching appearance aroused my curiosity. The poster’s main message was to ask whether I had a reached a surfeit of frustration with not being heard and if so, to make contact with the Morecambe Bay Poverty Truth Commission. Following the encounter at Eggcup where I had felt bracketed as ungrateful, lazy and potentially the most damaging for any middle-aged woman, difficult, I stood in need of being heard. A hugely traumatic year had served to rob me of my confidants and as such, lonely tears of frustration were continually bubbling below the surface.

Blinking them away, I read the text on the poster which suggested making contact by email or telephone to participate in a conversation on poverty, provided I had lived experience of it. I captured the image of the poster and returned home ruminating on the verbal exchanges I had just undertaken whilst attempting to choose some groceries and their broader meaning in discourses about deprivation. I was really interested in the triple disadvantage of poverty, being female and disabled. This intersection is rarely examined and is a personal interest, but I am fully aware there are different issues for men whose lives are blighted by physical or mental poor health and economic deprivation, especially in terms of housing and access to benefits.

Blinking them away, I read the text on the poster which suggested making contact by email or telephone to participate in a conversation on poverty, provided I had lived experience of it. I captured the image of the poster and returned home ruminating on the verbal exchanges I had just undertaken whilst attempting to choose some groceries and their broader meaning in discourses about deprivation. I was really interested in the triple disadvantage of poverty, being female and disabled. This intersection is rarely examined and is a personal interest, but I am fully aware there are different issues for men whose lives are blighted by physical or mental poor health and economic deprivation, especially in terms of housing and access to benefits.

Pejorative labels are applied differently to the sexes but with equally damning effects and unfortunately, there are many of those in voluntary roles in local initiatives or salaried government positions who are happy to ascribe responsibility to the individual rather than the system.

I wanted to share elements of my story and having been unable to put my education to any use outside of domestic life, I was interested in research projects to help resolve social injustice. This study appeared to be concerned with garnering the issues for those living in poverty, and although I was sceptical about whether it was a tick box exercise to usher in a Labour government, or to feather someone else’s nest by providing original material for a master’s degree or doctorate, I knew that not at least attempting to find out could be doing myself and others with similar issues a great disservice.

Within a week, I had made contact and I arranged to meet Ally Mackenzie for coffee. Still sceptical that my story was simply research fodder, I prepared carefully for the meeting because if I was about to be exploited, I had no intention of appearing uneducated or ill-informed. Ally was punctual and we sat drinking coffee while she explained some of the background to the commission and the ways in which it had positively impacted the lives of others, taking them from desperate stories of homelessness, addiction and isolation to tenancies, employment and friendships. I was greatly impressed by her respectful and genuine interest, and I began to speak to her about some elements of my experience.

I was then invited to a gathering of northern Poverty Truth Commissions at the Storey Gallery, Lancaster. Again, I was apprehensive about this. I had attended various training and participation groups over the years and my main concern was that for someone, somewhere it just represented a few hours out of the office with a prepossessing buffet and revolutionary but empty soundbites. It reminded me in hindsight of Animal Farm where the pigs require extra food and privileges to allow them to do the hard work of drafting rules. Thankfully, my fears were unfounded, and I was pleasantly surprised to observe real conversations between civic and community commissioners and a palpable environment of mutual respect.

I felt sufficiently welcome to participate in offering the findings of our commission to the rest of the network who were in attendance. Meeting Phil Sykes, the other facilitator of the commission was equally pleasant, and his sincerity was as obvious as Ally’s. The food was sufficient and well received but this was no exercise in gluttony or impressing colleagues with the ability to detect the truffle oil used to infuse the organic olives (which I have previously encountered). Rather, this seemed to involve simplicity and economy, but with no room for greed, which was a heartening introduction to the ethos of Morecambe Bay Poverty Truth Commission and the network itself on a wider level.

Regular, frequent meetings of the commission help to foster strong bonds within the group and sharing food together helps to generate a sense of intimacy which allows us to gain an understanding of the similarities and differences in our experience of living in poverty. Since I joined the commission in June, there have been many opportunities available to participate at a group or local level, such as free SIM cards to allow better communication, along with taking part in protest marches, either physically adding one’s own voice to the throng or simply adding to the numbers. The National Gathering event held in Derby was wonderfully charged, illustrating commonalities between groups, and providing chances to learn from each other about priorities, experiences and successes.

There were representatives at the gathering from our local civic commissioners who all brought warmth, respect and a different set of skills and perspective in terms of the issues discussed. I was pleasantly surprised to observe and hear the depth of frustration they felt when dealing with particular problems, but also the sense of optimism permeating their work. This didn’t seem to be rooted in idealism, but a genuine belief in their ability to effect change. In turn, this enthusiastic approach to the future is infectious, particularly when propounded by those with an ability to directly influence and implement policy.

The full commission’s energy is tangible and to quote a well-worn phrase, it is truly more than the sum of its parts. Each of us, whether a civic or a community commissioner is now using the positive label of ‘truth teller’, even though the honest nature of different circumstances is less than desirable.

From a personal perspective, I have greatly enjoyed meeting with civic commissioners, both at the National Gathering and the recent evening workshops at Lancaster and Morecambe College. This has led to me meeting with some of them in the pursuit of community projects at their suggestion and with support. I have met some others at different points, and some were completely new faces.

Looking ahead, in addition to the area of mental health which I am keen to be involved in owing largely to academic interests, I would hope to see a fairer framework realised for those facing homelessness at the end of a relationship, especially those with children who according to current rules are faced with very particular obstacles. I firmly believe that this negatively impacts children more than ever and as a society we may pay a heavy price for brutalising our children with the example of rendering one parent homeless or in utterly unsuitable accommodation.

Radio 4’s Today programme recently delivered a most concerning nugget of information, stating that children underserved by society are likely to be twenty months behind their more advantaged peers in terms of learning. Consequently, this negatively impacts their employability and therefore potential earnings, making any attempt at redistribution of resources an investment rather than an expensive measure. Although the topic discussed was access to free school meals, the same point is arguable in each area of deprivation.

With an eye to the winter months ahead, I have some serious concerns about the role of journalism in the dangerous resurgence of moral panics about benefit claimants, particularly the disabled, those unable to prioritise shopping for groceries and those looking for work. The Lancaster Guardian recently ran articles stating how much various disabilities are worth to claimants of Personal Independence Payments and Employment and Support Allowance, which is practically guaranteed to encourage resentment towards those with disabilities.

In conclusion, I greatly appreciate being a part of the Morecambe Bay Poverty Truth Commission and I admire the facilitators, my fellow community commissioners and those from the civic community. My hope is that as a group we can identify and help to resolve the issues around various types of poverty which scourge our society, since nothing about us, without us, is for us.